Hello. Welcome to Words about Numbers, the bloggy goodness part of our site.

In this, our first post of all time, I want to talk about our goal with data science, and the final message I want to convey is:

Data science does not exist merely for the production of answers.

Its goal is to encourage people into action.

As a guiding light, the most important question to ask is:

“What are we trying to achieve here?”

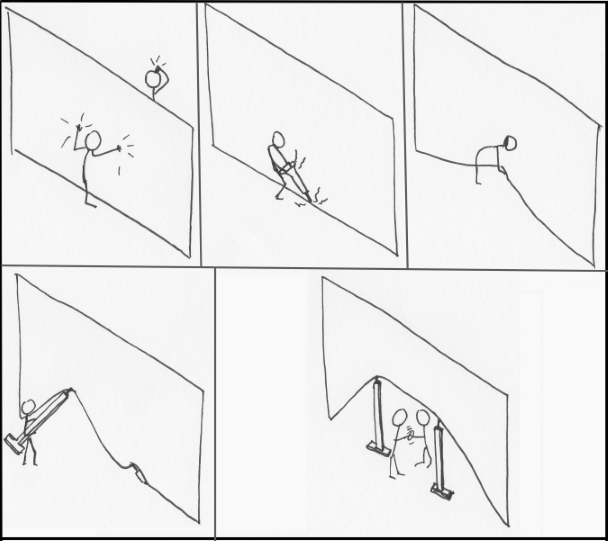

And to answer this question, you need good communication between parties who often speak different “languages”, in many cases without realising it.

You might think of the outcomes of data science in terms of nouns and verbs.

nouns = things

verbs = actions

In a story, the right verb can be very powerful. Nouns help to fill the picture – they serve the story. But the verbs push the action along – they drive the story.

Linking back to people, and specifically to their roles in the workplace, we might call the people doing the analysis and coming up with the answers, the “staff” and the people who can effectively drive change, the “managers”. But, while we might easily identify with this divide, I’m not fond of using the “management” and “staff” designations. I’ve worked many jobs where this line was very fluid, and under the right conditions fluidity works very well.

I prefer the terms “language of money” and “language of things”.

People who spend their working hours looking at schedules and budgets know intuitively that all this hard analysis work has to help keep the business ticking along. They speak the “language of money”, and they’re looking for the “verbs”.

People who speak the “language of things” are asked to focus on answers: whether true or false, percentages, efficiency values, etc. These are all “nouns”, and they’re the subject of the day’s work.

Problem is, a while ago the world got complicated. It’s been said that the last person who worked in technology who understood all the tools they used, was Galileo. Few people speak both languages fluently.

Where do you identify on the money/things divide?

Do you want to talk to people on the other side of this divide, and know you’re being understood?

How often do you feel frustrated that you’re not being understood?

Take note each time it happens and remember: Maybe they’re not understanding you because you’re not speaking their language.

Doing it right starts with clarity of purpose.

When this communication gap gets bridged, a lot of good things can happen, and happen quickly.

“But”, I hear a collective voice say,

“I’m here to do my job, not teach it to people who will never do it.”

“I don’t have time, and neither do they.”

There’s a somewhat cynical line: “There’s never time to do it right, but there’s always time to do it over.”

Doing it right starts with clarity of purpose. Granted, the story and goals might evolve in the face of new information. They should.

Clarity doesn’t mean having all the answers in advance. It means “frank honesty about the goals”. And this can avoid a mountain of rework – something generally known to be one of the biggest time-and-money-eaters of a project.

Clarity of purpose > less confusion, less frustration, more co-operation, more satisfaction, more time to breathe and think > less rework, higher quality of time usage, more space to innovate > Higher profit, Happier staff

So, How?

How do people with different experiential backgrounds, different drivers and ideals, different “languages”, communicate?

The quickest way to explain your point of view is often to start with asking someone else theirs. Then listen carefully.

For those who speak the language of money: When you want answers, explain what will be done with them. Every single time. You’re talking to people who think that their answer will have a clear meaning in terms of action. Often it doesn’t, but this ambiguity is actually hard for them to spot if they haven’t been thoroughly briefed on the “money” side of the picture.

For those who speak the language of things: Remember it doesn’t stop with the noun. The answer to, “What is this?” should always start (before the analysis) and end with, “What do we do with it?”. The noun part is usually an answer given by the analysis, but the verb is part of a discussion.

The quickest way to explain your point of view is … asking someone else theirs.

Each person needs to remember that it is very unlikely that they alone have the full picture of what it is that they are trying to achieve. Together, you need to ask:

“Why are we doing this?” and

“What will be done with the results?”

i.e.,

“What are we trying to achieve here?”

I’m usually a “things” person, and taking the time to understand the goals of the analysis in advance has always been time well-spent; it’s saved a lot of frustration and rework. “What are we trying to achieve here?” is a question I write on a card and stick to the wall above my desk, to remind me. It’s a good question to ask at the start, and to keep asking.

It sounds simple, doesn’t it, to say that good things happen when people understand people, and they can see each other’s goals? It’s a simple thing to say, and yet it isn’t easy to do. It’s another in a long line of the challenges that keep us performing and growing – a necessary one if our goal is to work smarter. Which, of course, is the final goal of data science, right?

Leave A Comment